From Quarantine Islands to QR Codes: How Public Health Has Managed Mobility in Outbreaks

The politics of borders, bodies, and the enduring illusion of control

I teach a course on the history of public health to undergraduate and graduate students at Brown University’s School of Public Health. I’ve been writing my reflections after each session, and thought I would start sharing some of them here. A link to the course syllabus is available on my website.

The apparatus to oversee and manage human mobility out of concern for infectious threats is one of the oldest and most indelible of all public health tools. Few interventions have left such a durable imprint on how we think about protecting societies from disease. Though many of the tools of modern public health—vaccines, antibiotics, digital surveillance systems—are relatively recent innovations, the practice of managing mobility through quarantine is centuries old. It has survived not only because it feels intuitive but because, at moments of crisis, it satisfies the deep political need to act.

Ragusa and the Origins of Quarantine

The word itself—quarantine—emerged in 14th-century Italy. In 1377, the authorities of Ragusa (now Dubrovnik, in southern Croatia) faced waves of plague threatening to enter their bustling Adriatic port. Trade was the lifeblood of the city, but so too was the fear of infection. Ragusa’s leaders devised a simple but radical solution: ships arriving from infected areas would be required to wait offshore for thirty days before landing. This “trentino” was later extended to forty days—the quarantino, from which we derive quarantine.

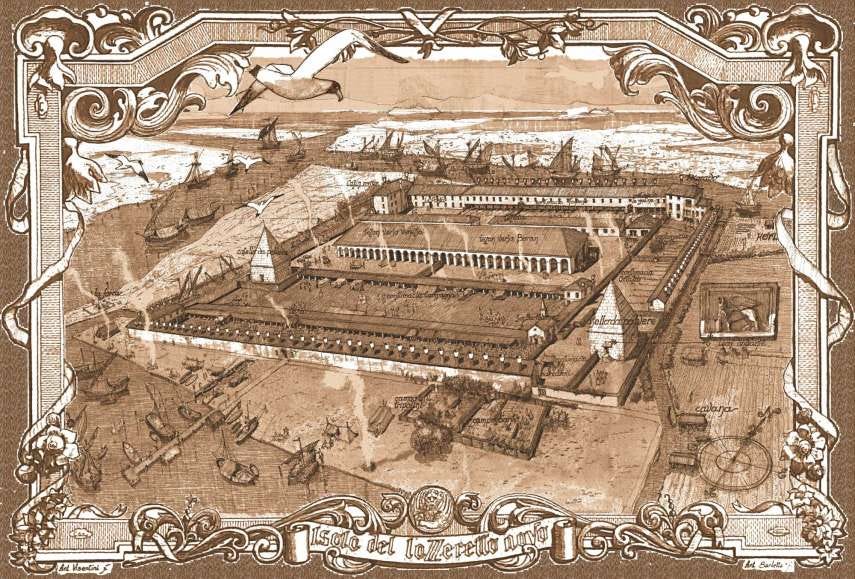

A few decades later, Venice, the true crossroads of Mediterranean commerce, formalized this system on an even larger scale. Venetian authorities created lazaretti—quarantine stations on islands outside the main city—where travelers and goods could be detained. The lazaretti were part medical facility, part prison, part warehouse. They represented not just an effort to separate the sick from the well but an early attempt to manage the risks of global interconnection. Venice understood that commerce brought both wealth and peril. Even if people did not yet think about “germs” as we do today, they recognized that the arrival of strangers sometimes preceded outbreaks.

These early experiments were not guided by scientific certainty. They were shaped by necessity, anxiety, and the recognition that something had to be done. The lazaretti were imperfect but enduring symbols of how societies tried to exert control over invisible threats.

The Persistent Logic of “Doing Something”

That basic impulse—responding to disease by restricting movement—has echoed across centuries. When the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 was first reported by South African scientists in late 2021, countries around the world rushed to restrict flights. The United States barred travelers from southern Africa, even though the variant was detected in Europe just days later and undoubtedly already circulating within our own borders. The measures were almost certainly too late to stop the spread. Yet the instinct remained the same as in Ragusa: faced with a new and frightening threat, political leaders felt compelled to act, to demonstrate vigilance by constraining mobility.

The durability of quarantine reveals less about its proven effectiveness than about its political and symbolic power. For rulers in Renaissance Italy, as for presidents in the 21st century, border controls and movement restrictions signal responsibility, authority, and action in the face of uncertainty.

Early Bureaucracies of Trust

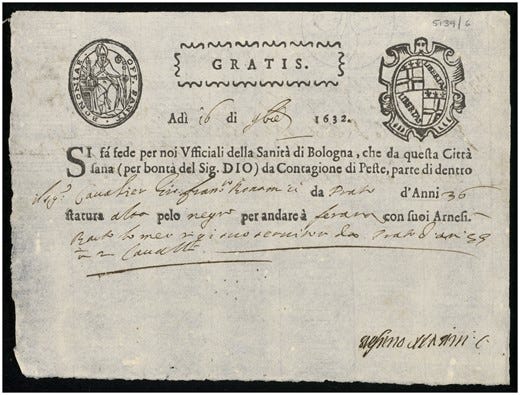

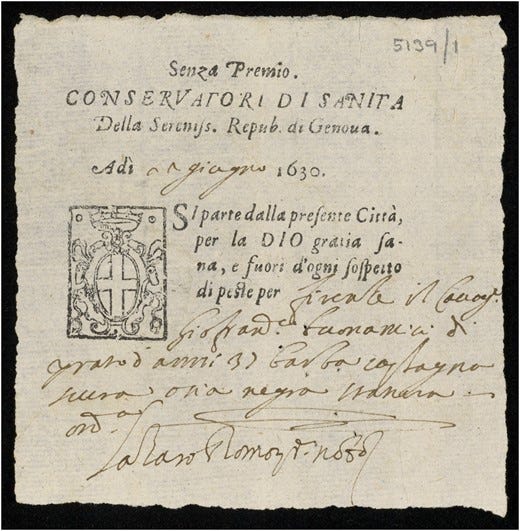

During the Middle Ages and into the early modern period, the threat of plague was a constant background reality. In times of heightened outbreaks, authorities cobbled together patchwork systems to reassure neighbors and trading partners. One innovation was the introduction of health passes—documents certifying that their bearer came from a place free of plague.

These early passes did not carry names, since literacy was limited and names were less stable identifiers than physical characteristics. Instead, they described individuals by height, hair color, and distinguishing features—attributes that could not easily be falsified. The passes were primitive forms of what we might today call “biometric data.” They reflected a nascent system of bureaucratic trust, a way of certifying health across uncertain and porous borders.

In this small way, public health became an early driver of state record-keeping. The desire to manage disease seeded the emergence of bureaucratic oversight that would later expand into passports, identity cards, and entire systems of population surveillance.

From Local Practices to International Negotiation

By the 19th century, the stakes of mobility control had grown dramatically. Global commerce and steamship travel shrank distances and sped up the circulation of both goods and pathogens. At the same time, scientific debates about contagion complicated decision-making.

Sanitationists argued that diseases like cholera arose primarily from local environmental conditions—foul water, poor hygiene, urban filth—rather than from person-to-person contagion. Others, increasingly persuaded by mounting evidence, insisted that diseases could be imported and spread by travelers. Without consensus, port authorities around the world adopted inconsistent policies. Some required lengthy quarantines; others imposed none. Traders and shipping companies complained bitterly about the unpredictability, which threatened commerce.

In 1851, frustrated by this chaos, dozens of nations convened the first International Sanitary Conference in Paris. Their goal was not simply to stop disease but to create clarity and uniformity: who would be quarantined, under what conditions, and for how long? Though the delegates failed to reach binding agreement, the very act of meeting signaled a new era: managing disease was no longer just a local or national affair. It was becoming a matter of international negotiation.

The Long Road to the International Health Regulations

The 1851 Paris conference was the first of many. Over the next century, nations repeatedly convened ad hoc sanitary conferences to hash out protocols. The debates were messy, protracted, and often inconclusive. But gradually, norms coalesced. The recurring challenge was balancing two competing imperatives: preventing the spread of disease while minimizing interference with trade and travel.

That balancing act remains central today. Indeed, the modern International Health Regulations (IHR)—first drafted in 1969 and substantially revised in 2005—explicitly state their purpose: to prevent the international spread of disease while avoiding “unnecessary interference with international traffic and trade.”

The conferences also seeded institutions. In 1907, the Office International d’Hygiène Publique (OIHP) was founded in Paris as a permanent body to oversee quarantine regulations and share epidemic intelligence. The OIHP was a proto-World Health Organization. It collected data on outbreaks, advised governments, and embodied the recognition that health threats crossed borders in ways that demanded collective oversight.

After World War II, in the spirit of global cooperation, the World Health Organization was established, and the OIHP’s functions were subsumed into it. The International Sanitary Regulations of 1951 later evolved into today’s IHR, which require member states to build surveillance capacity and to notify WHO of events that might constitute a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern.”

This system, imperfect as it is, represents one of the most ambitious forms of international cooperation in public health. That it exists at all is remarkable, given the centuries of fragmented and ad hoc responses that preceded it.

Fragility of the System

Yet the system is also fragile. International agreements depend on political will and trust. When the United States first threatened to withdraw from WHO during the COVID-19 pandemic, it shook the foundations of global cooperation. In the second Trump administration, the U.S. has moved to do so yet again, withholding funding for the WHO and isolating ourselves on the world stage.

Once major powers retreat from collective structures, the incentive for others to detect and report outbreaks diminishes. Why share uncomfortable truths if cooperation is eroding and the rewards are unclear?

The very logic of the IHR—balancing transparency with economic stability—creates perverse incentives. Countries that fear economic punishment from travel bans may hesitate to report outbreaks promptly. South Africa’s swift and transparent reporting of Omicron, for instance, was met with immediate border closures, a response that risks discouraging similar openness in the future.

Entrenchment of Quarantine

All of this raises a deeper question: are quarantine and travel restrictions too entrenched to question? Despite centuries of mixed evidence, they remain the reflexive response to emerging threats. Politicians announce border closures; public health leaders accept them as a given. Rarely do we conduct rigorous retrospective assessments of whether such measures truly altered the course of outbreaks. Even when evidence suggests limited benefit, practice seldom changes.

Quarantine, in other words, is not just a tool. It is part of the cultural and political DNA of public health. Its longevity makes it hard to imagine a world without it—even if its utility is far less certain than its symbolism.

Parallels and Inequities

The management of mobility is never neutral. Restrictions fall unevenly across societies, often deepening existing inequalities.

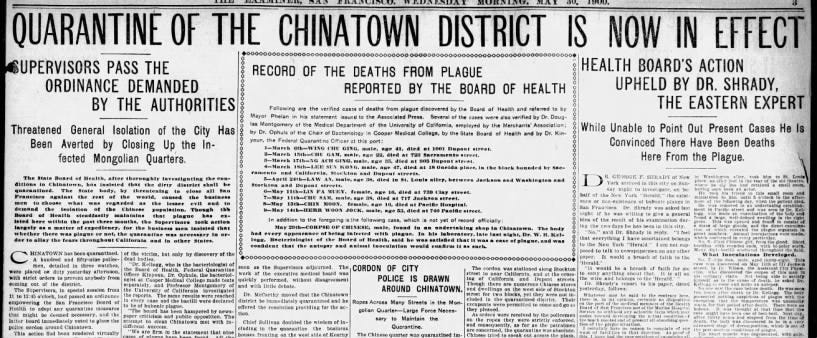

In the United States at the turn of the 20th century, Chinese immigrant communities in Honolulu and San Francisco were subject to mass quarantines during plague scares. Entire neighborhoods were cordoned off, while white residents were largely exempt. Quarantine became a vehicle for racialized exclusion, cloaked in the language of health protection.

The same patterns recurred in COVID-19. As the wealthiest New Yorkers fled to second homes, lower-income communities—often composed of essential workers—remained behind, more exposed to both infection and the burdens of lockdown. The book The Rich Flee and the Poor Take the Bus captured this divide: mobility restrictions are always easier to bear when one has alternatives.

The logic of controlling movement also echoes the brutal history of slavery. Enslaved Africans’ every movement was surveilled and constrained. Pseudo-medical diagnoses such as “drapetomania”—the supposed mental illness causing slaves to run away—medicalized the denial of freedom. This grotesque history reminds us that controlling mobility has long been intertwined with systems of domination, stigma, and inequality.

From Collective to Individual Blame

A dramatic shift occurred in the late 19th century with the rise of bacteriology. Robert Koch’s identification of the tubercle bacillus in 1882 seemed to confirm that specific microbes caused specific diseases. Suddenly, contagion had a tangible agent. This scientific revolution transformed not only medicine but also social attitudes.

Tuberculosis, once romanticized as the “white plague” of poets and artists, became a marker of poverty, filth, and immigrant otherness. Responsibility shifted from society to the individual. No longer was disease simply a collective hazard tied to shared environments; it was a personal failure of hygiene and morality. This reframing intensified the desire to identify, isolate, and control “risky” populations through quarantine and surveillance.

Edwin Chadwick’s earlier sanitary reforms, rooted in the recognition that everyone’s health was interdependent, gave way to a narrower focus. The bacteriological paradigm did not erase the need for sanitation and clean water, but it made it easier for societies to stigmatize the sick rather than reform the structures that produced vulnerability.

Workarounds and Resistance

Just as early plague passes could be forged or misused, modern digital health passes are not foolproof. During COVID-19, fake vaccination cards proliferated. QR codes and digital identifiers promised unforgeable security, but entrepreneurial fraudsters found ways around them. The history of quarantine is thus also a history of evasion, resistance, and workaround. Wherever states build systems to manage movement, individuals and groups find ways to navigate around them.

Enduring Ambivalence

What emerges from this long history is ambivalence. Quarantine and travel restrictions are blunt tools, born of fear and necessity, sustained more by habit and politics than by science. They have been bureaucratized into health passes and digital apps, and justified by centuries of precedent. Yet outside of limited circumstances often requiring drastic enforcement, their actual effectiveness remains contested.

Perhaps this is the paradox of mobility management: it is both indispensable and insufficient. Indispensable because it satisfies the need to act, to draw lines of protection. Insufficient because it rarely solves the deeper problems—poverty, inequity, fragile health systems—that make societies vulnerable in the first place.

Conclusion: Questioning the Apparatus

The control of mobility is one of public health’s oldest inheritances. From plague passes describing hair color to QR codes on smartphones, from lazaretti on Venetian islands to WHO regulations in Geneva, the throughline is unmistakable. Each generation retools the apparatus, but the core impulse remains the same.

The challenge for the future is whether public health can critically reassess this inheritance. Is quarantine too deeply woven into our imagination to be questioned? Are border closures so expected that their absence would seem like neglect? And if these tools ultimately undermine trust in public health by proving ineffective or inequitable, what alternatives could we envision?

As we grapple with these questions, history offers both caution and insight. Quarantine has never been inevitable, even if it feels natural. It has always been shaped by politics, inequality, and the ever-present need to do something. Recognizing that may be the first step toward imagining something better.

Hi Craig! I’ve been on here for about 2 weeks, and I’m trying to meet new people.

You share some interesting posts, so I thought I’d drop a comment and introduce myself with a article, I hope that’s okay friend:

https://open.substack.com/pub/jordannuttall/p/the-plague-in-asia?r=4f55i2&utm_medium=ios